Products You May Like

I’m not sure I trust the Page of Cups. As imagined by Pamela Colman Smith and A.E. Waite in the 1909 Rider-Waite Tarot, he’s a cocky young man in a floral tunic, standing by the seashore hefting a goblet. There’s a fish peeking out of the goblet and the Page appears to be gossiping with it, perhaps sharing a joke about the artist, because honestly, what kind of artist paints a guy talking to fish. Or is he thinking about offering us the cup? The set of his jaw is ambiguous.

When drawn in an upright position, the Page suggests a flash of inspiration reeled from the mind’s ocean, or a dazzling opportunity. In this guise, he’s been a good friend to Ami Y. Cai, a game creator and illustrator from Kentucky – though in her first Tarot deck, Stephanie Pui-Mun Law’s Shadowscapes Tarot, the symbolism has been flipped around a little, the Page depicted as a mermaid peering into a steaming bowl. “Sometimes sparks come to me through conversations, or while I’m doing something else,” Cai tells me over Zoom. “So when I see the Page of Cups, I know that a creative opportunity is coming my way.”

Every Tarot card has its “reverse” interpretation, however. Draw the Page of Cups upside down, and the joy of insight becomes jealousy and stagnation. “My biggest fear growing up as a creative is someone stealing my idea,” Cai says. “But there’s a downside when you cultivate an idea too long in this secret box – your idea will sour if it’s not given air. So when I see the Page of Cups in reverse, I get the feeling that I need to be more wary of the pros and cons of keeping it private.” It’s a familiar dilemma for artists of all stripes. “If you constantly go to others for feedback, how many of your ideas are actually yours?”

Cai doesn’t credit Tarot with the literal power to determine one’s fate. She treats it as a means of self-illumination and questioning, “of cracking a door that you didn’t realise is there – you can decide to go through the door, you can decide to close the door.” As an Asian American teenager in a “very white-cultured” area, Tarot was a way of exploring both her own heritage and other cultures. “Divination was something my mom was aware of, and Chinese divination is done very differently than in the West. I did a lot of research into how divination has been – I don’t wanna say cultivated, but it’s flourished in different ways around the world.”

The Page also helped Cai break into game development. In 2019, she sought a Tarot reader’s advice about a big grant project she’d been offered – an enticing, but anxiety-inducing prospect while finishing school and finding jobs in whirlwind New York. “And when I got the reading, it was an upright Page of Cups.” The grant project led to her first game design role. And now, she’s the art director on Cartomancy, a whole anthology of Tarot-themed videogames, designed by a host of modern-day conjurers that, much like Tarot itself, hail from all across the world.

Tarot dates back to at least 15th century Italy, though its precise origins are unknown. Over hundreds of years it has slowly dispersed across Europe and overseas, always changing. Today, there are hundreds upon hundreds of interpretations of the “standard” Tarot’s 78 extremely open-ended card concepts: botanical and animal-themed Tarots; decks based on movements such as Art Nouveau; licensed Tarots for The Nightmare Before Christmas and The Legend of Zelda; satirical decks featuring Nixon and Roosevelt; slapstick decks made up of paintings of rubber chickens.

We associate Tarot with prophecy and personality-reading, but that’s not why Tarot became ubiquitous – it wasn’t till the late 18th century that fortune-tellers and organisations such as the Order of the Golden Dawn began using Tarot as a mystic instrument. The reason for Tarot’s spread is that Tarot is a game. Take away the Major Arcana – a triumphal procession of 22 allegorical face cards – and you’ve got something like the vanilla deck we use to play Poker or Solitaire: four suites of aces, number cards and court cards, albeit with one extra, the Knight.

People still play games with Tarot. “I think we use them in my hometown, Genoa, but also in Naples,” says Federico Fasce, a game design lecturer at Goldsmiths University and one of Cartomancy’s contributing developers. “There are many games that use this slightly extended kind of deck, usually games that are based on trumps – trying to get as many cards as possible, with different combinations of cards to score more points, stuff like that. They tend to be very simple games, but in Italy it’s pretty common to see people playing these games. It’s a bit of an old people pastime.” (Fasce himself was introduced to Tarot by his aunt.)

If the Tarot’s Minor Arcana of court and number cards lend themselves more readily to mainstream card games, it’s the celebrities of the Major Arcana who have fired the imaginations of videogame developers. The Major Arcana is a bottomless work of procedural narrative – a re-arrangeable lifestory that functions like a magic mirror. The first card in the series is the Fool, an everyman portrayed by Waite and Smith as a jolly wayfarer with the sun behind him and a cliff edge right under his outstretched foot. The other cards represent adventures, triumphs and setbacks experienced by the Fool on his trek towards the concluding figure of the World.

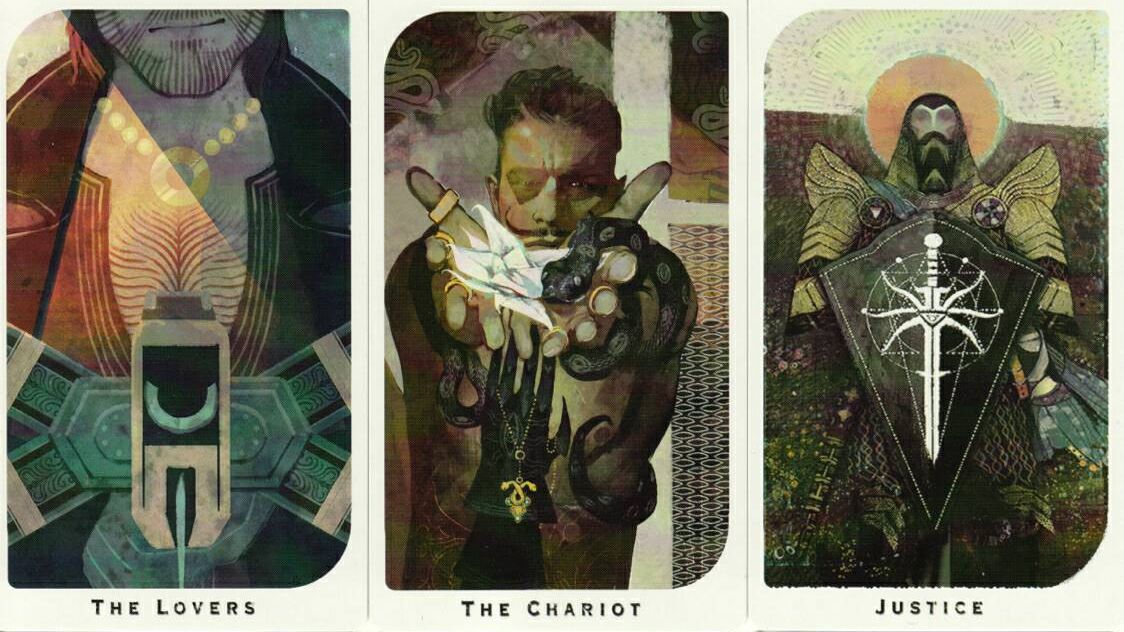

Some videogames riff on this oracular narrative structure explicitly. Sayonara: Wild Hearts, for example, turns the Fool’s journey into an album of musical boss battles (Simogo, alas, declined to be interviewed for this piece, citing a lack of real expertise in Tarot). Others evoke the idea of a live lived through the cards more obliquely. My favourite bits of Dragon Age: Inquisition, for example, are its Tarot-style character portraits, which transform as you get to know your companions and unravel their backstories.

The Cartomancy anthology is based on the Major Arcana alone, which sadly means that Cai’s mate the Page won’t get a credit. Each game is an interpretation of single card. Contributors include Tanya X. Short of Boyfriend Dungeon developer Kitfox, who has teamed up with Brett Ellison to adapt the Emperor card, and Colorfiction, purveyor of mazy, occult train journeys and woodland walks, who is doing Death. It’s a “global conversation”, Cai adds, involving “a lot of marginalised voices – different genders, sexualities, races and locations.”

“There are so many cards with very drastically different meanings, upright and reverse.”

Each game blends upright and reversed meanings into one, partly because it would be impractical to make two games per card, but also because the combination fosters a useful tension. “That [may help decide] what the conflict of the game is,” Cai notes. “What the reward is, the narrative flow of the game, because there are so many cards with very drastically different meanings, upright and reverse. Though there are some cards that are equally bad, upright and reverse.” Among the latter is the Tower, which is being adapted for Cartomancy by Elliot Herriman, Rachel Morgan and Sol Martínez-Solé. “I know a lot of people outside Tarot are fearful of the Death card, but honestly, the Tower is my least favourite,” Cai says. “The Death card can mean something is new, something has passed. The Tower is like, everything’s in ruins.”

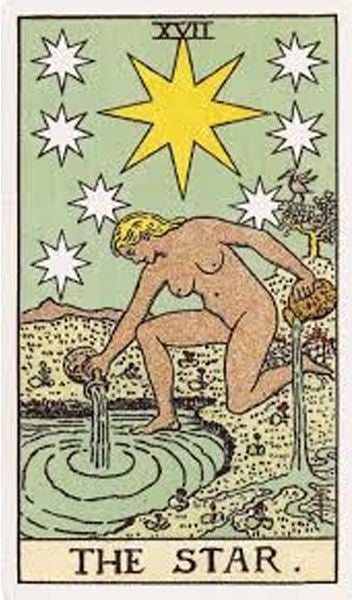

In the narrative of the Major Arcana the Tower is followed by the Star. The Rider-Waite deck renders this card as a kneeling woman with one foot in a pool, the other on land. Where the Page of Cups clutches his goblet a little jealously, the woman pours water from jugs in both hands; she seems to be filling the pool and tending the soil simultaneously.

“Everybody fears the Tower, because it just kind of breaks everything, but it’s also a sort of creative destruction,” says Fasce. “And the Star kind of represents hope, because it comes right after. But I think it’s also about understanding how you deal with trauma and adversity, which I think is a really interesting message. It’s not just ‘oh, I’m hopeful things will go well’. It’s a more mature kind of hope.”

Fasce’s own Cartomancy project with Three of Cups Games treats the Star as a symbol for “healthy communication and balance between your emotions, your intellect and actions” – one foot in the water, one on firm ground. It begins in misfortune and travels towards “a point of pure hope”, using the card’s different meanings to explore diverging understandings of trauma. “[The reverse isn’t] about the lack of hope. It’s like, there’s hope, but you are expecting things to happen without doing anything. You should be actively reaching.” Stars, Fasce adds, are woven into the words we use to describe knowledge and its absence. “’Desiderata’ comes from ‘missing the stars’, because the idea was that when sorcerers couldn’t read the sky, they couldn’t read the future. And so ‘desire’ is this lack of clarity of vision about what to do next.” ‘Consider’, by contrast, “comes from the Latin for ‘with the stars’ – it’s the moment when you actually use this this light to guide you.”

Like Cai, Fasce doesn’t believe in Tarot as a literal means of prediction. “But what I do believe is that these symbols are so universal, that it’s quite easy to just grab at them and make something deep inside you emerge.” The Cartomancy project aside, he uses Tarot as a personal imaginative aid and a pedagogic instrument for aspiring narrative designers. “One of the things that I teach students is to connect dots, put things together that don’t seem related. With Tarot it’s very easy to exercise that skill, because you can do a very simple three card spread and start building a story. It’s not just about discovering cards, but how they bleed into each other.”

Another game developer who teaches with Tarot is Char Putney, whose credits range from vast enterprises such as Balder’s Gate 3 to pungent smallscale works like Vitriol, an eldritch word puzzle developed with her partner Martin Pichlmair. Putney runs interactive fiction workshops in which she sometimes asks people to tell stories with Tarot cards, printing out and snipping up sheet upon sheet of Rider-Waite designs. While she enjoys seeing her students get excited about their discoveries, the point is partly to show that anyone can devise stories this way, and counteract “the sickness of thinking that it’s something pulled uniquely from within, that only belongs to them”.

Putney herself stumbled into the world of Tarot while studying classical and Biblical languages and literature at university. Hebrew proved especially helpful for a budding scholar of the occult. “All the Tarot cards have their own Hebrew letter association – everything to do with the Golden Dawn system of magic. And Victorian English magic is all like, segued through Hebrew verbs for some reason.”

One of Putney’s great fascinations is the Book of Thoth, a Tarot deck devised by the magician, self-styled messiah and rumoured secret agent Aleister Crowley, with cards illustrated by Freida Harris. Rather than just suggesting new designs, Crowley invented or modified card meanings to suit his own, rather feisty philosophical pursuits. “The World card is now the Aeon, because he’s really into the new Aeon,” says Putney. “We are going from the age of Osiris, which is the age of the dying god, the past of Christianity, and he’s the prophet of the new aeon, which is Horus. I don’t know if you’re into Grant Morrison’s comics, but Grant Morrison really pulls that whole thread very strongly through all of his work. The age of Horus is like the era of a child looking about with the building blocks of reality, rather than a stern father telling us what to do.”

In the spirit of Horus, Putney and her partner Martin Pichlmair once cooked up their own Tiphareth Tarot based on Crowley’s Thoth deck during a gamejam. “We basically remixed all of Crowley’s cards using GPT and a bunch of specific magical numbers that are very relevant to Crowley’s way of thinking and the Thelemite magical worldview.” Putney acted as human intermediary, curating bits of procedurally generated text into gorgeous prose poems, while Pichlmair spawned “not-so-sacred” geometry to accompany them using his own cryptic methods. “Doing that took us the whole weekend, and we went absolutely crazy, eating tortilla chips and drinking wine and cackling.”

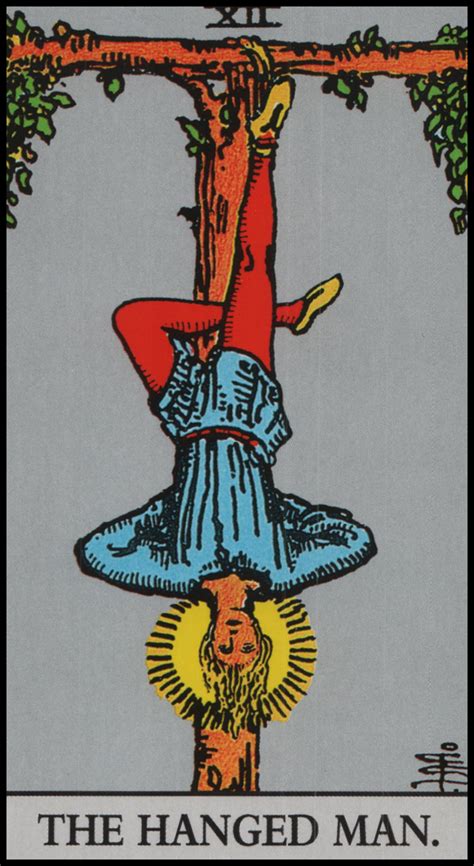

What card would Putney work with if she were developing a game for Cartomancy? Possibly the Hanged Man, who appears upside down – suspended by one foot, the other leg laid across his knee. As grisly as the card may sound, it’s an almost comical display: upend the card and he could be dancing a jig. Or as Putney suggests, doing yoga. “I teach this little yoga class every Tuesday night to a group of people on the internet, and we do this one pose, where you’re twisting your head and arms one way, and your legs the other. And there’s this moment where I just say, OK, let go of everything [because] you don’t realise that we’re holding our bodies in this really tense shape all the time.”

For Putney, the Hanged Man represents “radical acceptance of the reality of a situation”. Far from being a symbol of torture, he’s an odd yet calm perspective on horrible events. “If you look at very traditional interpretations of the Hanged Man, it’s always really dark and heavy, like sacrifice or self-sacrifice. But it’s really important that he’s not hanging by his neck!” It’s important, too, that the Hanged Man looks more thoughtful than anguished. “This used to be a punishment for traitors back in the 1500s – they would keep feeding them and giving them water until they died. So it’s pretty awful. But the idea is that he’s not dead yet. He still has options.”

Tarot is all about options, and there are countless left to explore as regards the cards discussed in this piece, even if you confine yourself to the symbolism of the Rider-Waite deck. They’ve certainly given me a few tools with which to re-examine my life, as yet another gloomy pandemic year drags to a close. The Page of Cups cautions me against hoarding myself and my projects – we all draw from the same, vast ocean, so maybe don’t obsess over a single fish. The Star tells me not to wallow in disaster, but she’s checked a little by the Hanged Man, who invites me to stand still and consider my surroundings anew.